Introduction

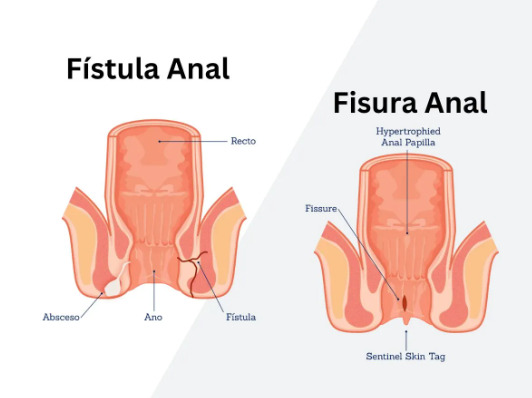

Internal hemorrhoids form inside the rectum above the dentate line, where pain-sensing nerves are absent, while external hemorrhoids develop under the skin around the anus where numerous pain receptors exist. This anatomical difference explains why external hemorrhoids often cause significant discomfort while internal ones may go unnoticed until bleeding occurs. The dentate line, located approximately 2-3 centimeters inside the anal canal, serves as the boundary that determines hemorrhoid classification and influences treatment approaches.

Both types result from increased pressure on rectal blood vessels, but their symptoms, examination findings, and treatment protocols differ substantially.

Anatomical Differences and Development

Internal hemorrhoids originate from the superior hemorrhoidal plexus, a network of blood vessels located above the dentate line within the columnar epithelium of the rectum. This tissue lacks somatic innervation, containing only autonomic nerve fibers that don’t transmit pain signals. The surrounding mucosa produces mucus for lubrication, and these vessels normally function as cushions that help maintain continence.

External hemorrhoids arise from the inferior hemorrhoidal plexus beneath the dentate line, covered by anoderm – modified skin rich in nerve endings. This squamous epithelium contains the same pain receptors, temperature sensors, and touch receptors found in normal skin. The external hemorrhoidal vessels connect with subcutaneous tissues and are anchored by connective tissue called the corrugator cutis ani muscle.

The dentate line marks the embryological junction between endoderm and ectoderm, explaining the different nerve supplies. Above this line, visceral nerves from the pelvic plexus provide innervation, while below it, somatic nerves from the pudendal nerve create sensitivity. This developmental distinction affects not only pain perception but also healing patterns and surgical approaches.

Blood supply also differs between the two types. Internal hemorrhoids receive arterial blood from terminal branches of the superior rectal artery, while external hemorrhoids are supplied by the inferior rectal artery. Venous drainage follows separate pathways too – internal hemorrhoids drain through the superior rectal veins into the portal system, while external hemorrhoids drain via inferior rectal veins into the systemic circulation.

Identifying Internal Hemorrhoids

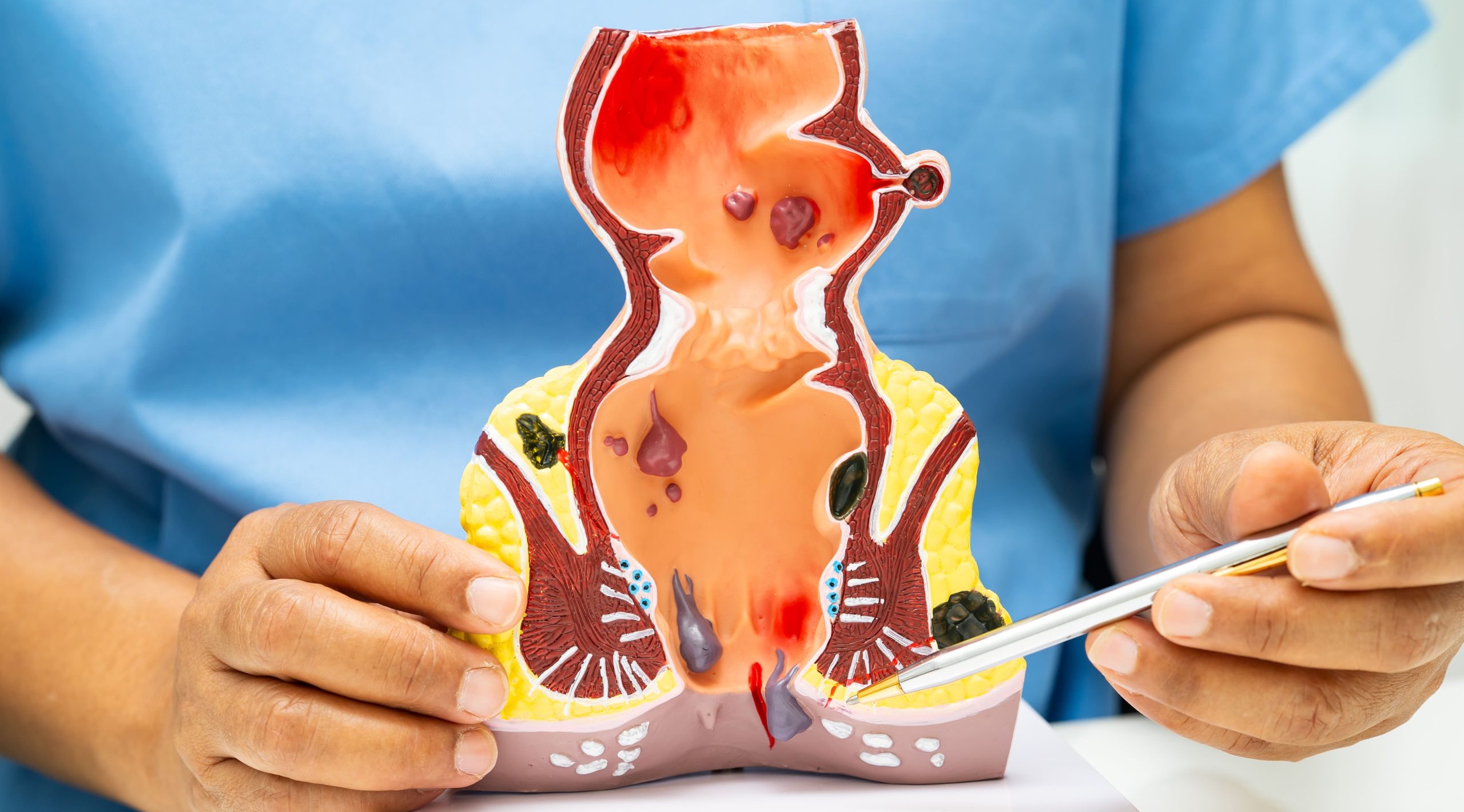

Internal hemorrhoids typically present with bright red blood on toilet paper, in the toilet bowl, or coating the stool surface. The bleeding occurs when passing stool traumatizes the fragile hemorrhoidal tissue, rupturing small vessels within the engorged cushions. Blood appears bright red because it comes from arterial vessels and hasn’t been digested or mixed with stool.

Prolapse represents the second major sign of internal hemorrhoids. Grade I hemorrhoids remain entirely within the anal canal. Grade II hemorrhoids protrude during bowel movements but retract spontaneously. Grade III hemorrhoids require manual reduction after prolapsing, while Grade IV hemorrhoids remain permanently prolapsed and cannot be pushed back inside.

Mucus discharge frequently accompanies internal hemorrhoids, particularly in grades III and IV. The exposed rectal mucosa continues producing its normal secretions outside the anal canal, leading to perianal moisture, itching, and skin irritation. Some patients notice mucus stains on underwear or experience a constant feeling of wetness.

A sensation of incomplete evacuation often develops as hemorrhoids enlarge. The swollen tissue creates a feeling of fullness in the rectum, even after bowel movements. Patients may strain repeatedly, attempting to empty what feels like retained stool but is actually hemorrhoidal tissue.

Internal hemorrhoids only cause pain when complications arise. Thrombosis within a prolapsed internal hemorrhoid creates sudden, severe pain as blood clots form within the hemorrhoidal vessels. Strangulation occurs when the anal sphincter traps prolapsed tissue, cutting off blood supply and causing tissue death if untreated.

Recognizing External Hemorrhoids

External hemorrhoids manifest as visible or palpable lumps around the anal opening. These swellings range from small, soft nodules to firm masses several centimeters in diameter. The overlying skin may appear normal, stretched, or discolored depending on the degree of engorgement and any associated thrombosis.

Pain characterizes external hemorrhoids, varying from mild discomfort during sitting to severe, constant throbbing. Activities that increase abdominal pressure – bowel movements, coughing, lifting – intensify the discomfort. The pain stems from stretching of the sensitive anoderm and pressure on surrounding tissues.

Thrombosed external hemorrhoids create acute, severe pain within hours of clot formation. The hemorrhoid becomes a firm, tender, purple-blue mass. Pain peaks within 48-72 hours, then gradually decreases over 7-10 days as the clot either resolves or ruptures through the skin.

Itching around external hemorrhoids results from several factors. Skin tags – redundant tissue remaining after hemorrhoid resolution – trap moisture and fecal matter. Chronic inflammation damages the perianal skin’s barrier function. Excessive cleaning in response to perceived uncleanliness creates further irritation.

Bleeding from external hemorrhoids occurs less frequently than with internal hemorrhoids. When present, blood appears after wiping and comes from tears in the overlying skin rather than the hemorrhoid itself. Thrombosed hemorrhoids may bleed profusely if the clot erodes through the skin surface.

Examination and Diagnosis Methods

Visual inspection reveals external hemorrhoids immediately, appearing as perianal swellings or skin tags. Acute thrombosis creates characteristic purple-blue nodules with tense, shiny skin. Chronic external hemorrhoids leave behind skin tags – loose folds of excess tissue that persist after the hemorrhoid shrinks.

Digital rectal examination allows assessment of anal tone, detection of masses, and evaluation of internal hemorrhoids that have prolapsed. The examining finger can identify the location and consistency of hemorrhoidal tissue, though grade I internal hemorrhoids often cannot be palpated. The examination also rules out other pathology such as rectal polyps or tumors.

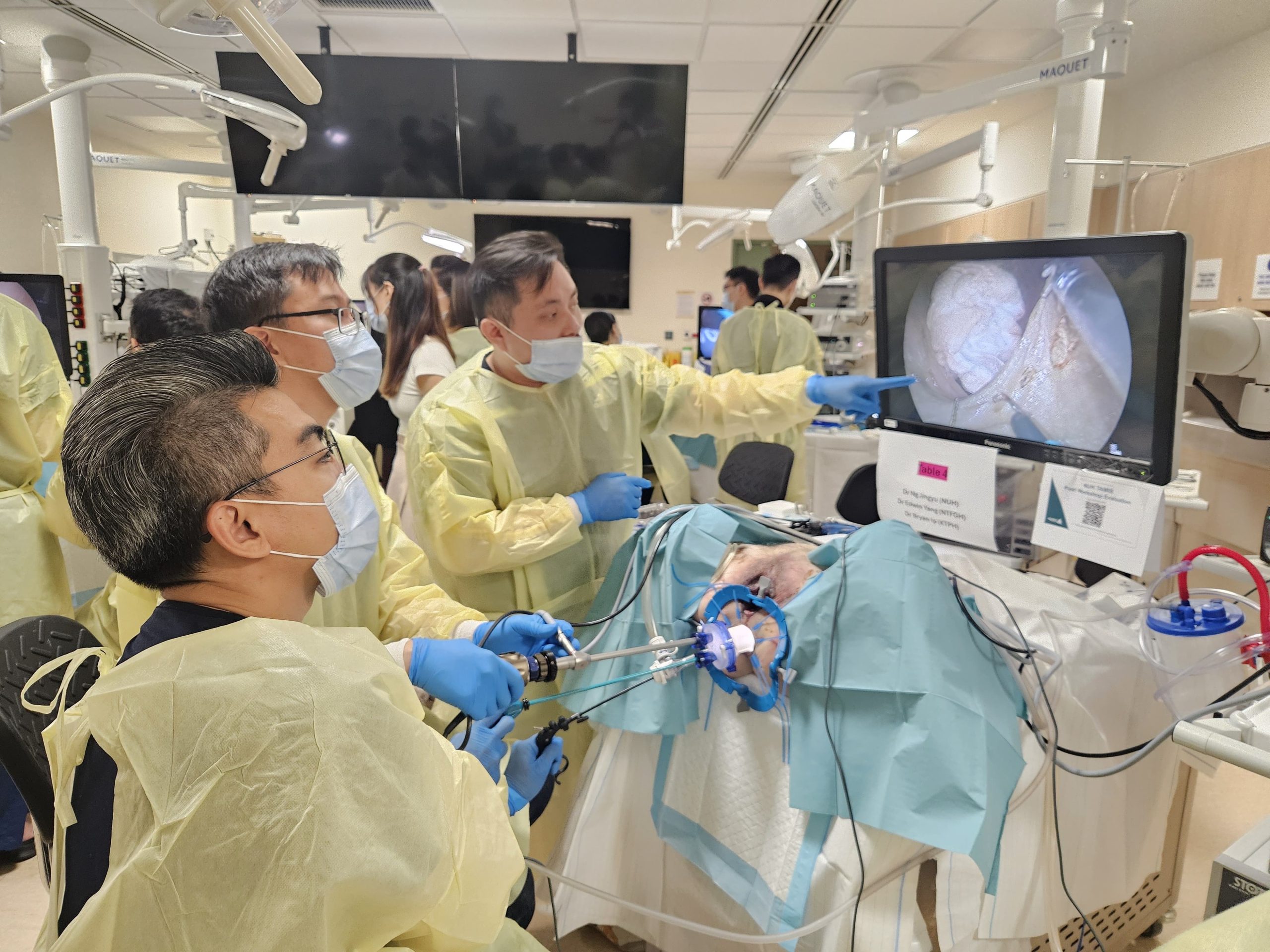

Anoscopy provides direct visualization of the anal canal and lower rectum, revealing internal hemorrhoids in their natural position. The anoscope, a hollow tube with a light source, allows inspection of hemorrhoidal size, location, and any associated inflammation or bleeding sites. The procedure takes 2-3 minutes and requires no sedation.

💡 Did You Know?

The anal cushions that develop into hemorrhoids actually serve an important function – they contribute to resting anal pressure, helping maintain continence for gas and liquid stool.

Proctoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy may be performed when bleeding persists despite hemorrhoid treatment or when patients are due for colorectal cancer screening. These procedures examine higher portions of the rectum and sigmoid colon, identifying other potential bleeding sources such as polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, or malignancies.

Colonoscopy becomes necessary for patients over 50 with rectal bleeding, those with family history of colorectal cancer, or when bleeding characteristics suggest a proximal source. Dark blood, blood mixed within stool, or constitutional symptoms like weight loss and altered bowel habits warrant complete colonic evaluation.

Conservative Treatment Approaches

Dietary fiber supplementation forms the foundation of hemorrhoid management. Psyllium husk, methylcellulose, or wheat dextrin can help soften stool consistency and reduce straining. Fiber works by absorbing water, increasing stool bulk, and accelerating transit time through the colon. A healthcare professional can advise on appropriate dosing and gradual introduction to minimize bloating and gas.

Adequate hydration enhances fiber’s effectiveness. Sufficient water intake helps prevent fiber from causing constipation. Warm liquids, particularly in the morning, may stimulate the gastrocolic reflex and promote regular bowel movements.

Sitz baths provide symptomatic relief through several mechanisms. Warm water relaxes the anal sphincter, reducing spasm and improving blood flow. Regular sessions may decrease pain and promote healing. Adding Epsom salts may enhance the anti-inflammatory effect.

Proper toilet habits prevent hemorrhoid progression. Limiting toilet time, avoiding reading or phone use that prolongs sitting, and responding promptly to defecation urges are recommended practices. Using a footstool to elevate knees above hips may optimize the anorectal angle for easier elimination.

⚠️ Important Note

Never attempt to lance or drain a thrombosed hemorrhoid at home – this risks severe bleeding, infection, and incomplete clot removal that worsens symptoms.

Topical preparations offer temporary symptom relief. Zinc oxide creates a protective barrier and has mild astringent properties. Hydrocortisone cream may reduce inflammation when used as directed by a healthcare professional. Lidocaine or pramoxine-containing products provide local anesthesia. The appropriate application method and duration should be determined by a qualified healthcare professional.

Medical and Surgical Interventions

Rubber band ligation treats grade I-III internal hemorrhoids by placing elastic bands at the hemorrhoid base using a special applicator. The band cuts off blood supply, causing the tissue to necrose and fall off within 5-7 days. The procedure takes minutes in clinic without anesthesia since application occurs above the dentate line where pain sensation is absent.

Sclerotherapy involves injecting a sclerosing agent into the hemorrhoid’s submucosa. The solution causes inflammation, fibrosis, and vessel obliteration. Treatment frequency and dosage should be determined by a healthcare professional. This technique may be considered for grade I-II hemorrhoids with bleeding as the primary symptom.

Infrared coagulation applies infrared light through a probe tip, creating controlled tissue destruction through heat. The treatment protocol should be determined by a healthcare professional. The resulting necrosis and fibrosis reduce hemorrhoid size and vascularity. Recovery involves minimal discomfort, with most patients returning to normal activities immediately.

Hemorrhoidectomy remains the definitive treatment for grade III-IV hemorrhoids and those failing conservative management. The Ferguson technique involves excising hemorrhoidal tissue and closing the wound with absorbable sutures. The Milligan-Morgan approach leaves wounds open to heal by secondary intention. Both techniques can achieve good results for symptom resolution.

Stapled hemorrhoidopexy, or procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids (PPH), uses a circular stapling device to excise a ring of redundant rectal mucosa above the hemorrhoids. This lifts prolapsing tissue back into normal position while interrupting blood supply. The procedure causes less postoperative pain than traditional hemorrhoidectomy since stapling occurs above the dentate line.

Thrombosed external hemorrhoid excision may provide relief when performed within 72 hours of onset. Under local anesthesia, the surgeon makes an elliptical incision, removes the entire clot and hemorrhoid, then either sutures the wound or leaves it open. After 72 hours, conservative management usually suffices as pain naturally decreases.

Prevention Strategies

Regular physical activity promotes healthy bowel function through multiple mechanisms. Exercise stimulates intestinal contractions, reduces transit time, and improves pelvic floor muscle tone. Aim for 30 minutes of moderate activity like brisk walking, swimming, or cycling on most days. Avoid prolonged sitting by taking hourly breaks to stand and move.

Weight management reduces intra-abdominal pressure on pelvic vessels. Excess abdominal weight increases pressure on rectal veins, particularly during straining. Weight reduction can improve symptoms in overweight individuals.

Pregnancy-related hemorrhoids benefit from specific modifications. Sleep on the left side to reduce pressure on pelvic vessels. Perform Kegel exercises to strengthen pelvic floor muscles. Use a donut cushion when sitting for extended periods. Apply cold compresses for acute swelling.

Avoid constipation triggers including low-fiber processed foods, inadequate water intake, and medications like opioids, anticholinergics, and iron supplements. When these medications are necessary, proactively increase fiber and consider stool softeners.

Proper lifting technique prevents sudden pressure increases. Bend at the knees, keep the back straight, and exhale during lifting rather than holding breath. Distribute weight evenly and avoid twisting motions while carrying loads.

Commonly Asked Questions

How long do hemorrhoid flare-ups typically last?

Acute external hemorrhoid thrombosis causes severe pain for 48-72 hours, then gradually improves over 7-10 days. Internal hemorrhoid bleeding episodes often resolve within 2-3 days with conservative measures. Prolapsed internal hemorrhoids may persist until manually reduced or surgically treated. Most uncomplicated flares respond to conservative treatment within one week.

Can hemorrhoids develop into cancer?

Hemorrhoids never transform into cancer – they are benign vascular structures. However, rectal bleeding attributed to hemorrhoids may mask colorectal cancer symptoms. Any rectal bleeding in patients over 50, bleeding with constitutional symptoms, or bleeding persisting despite hemorrhoid treatment requires thorough evaluation to exclude malignancy.

Why do hemorrhoids return after treatment?

Hemorrhoids recur when underlying risk factors persist. Continued straining, constipation, prolonged sitting, and increased abdominal pressure recreate the conditions that caused initial hemorrhoid development. Successful long-term management requires addressing these root causes through dietary changes, exercise, and proper toilet habits rather than treating symptoms alone.

Is hemorrhoid surgery painful?

Modern surgical techniques and multimodal pain management can reduce postoperative discomfort. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy causes less pain than traditional excision. Regional nerve blocks, long-acting local anesthetics, and scheduled analgesics control postoperative pain. Pain levels are manageable with prescribed medications.

When should I consult a healthcare professional about hemorrhoid bleeding?

Consult a healthcare professional for bleeding that soaks through pads, causes dizziness or weakness, or contains clots larger than 2 centimeters. Persistent bleeding beyond one week, dark or maroon blood, or blood mixed within stool rather than on its surface requires assessment. Any bleeding accompanied by fever, severe pain, or change in bowel habits warrants consultation.

Conclusion

Internal and external hemorrhoids require different treatment approaches based on their distinct anatomical locations. Conservative measures including fiber supplementation and proper toilet habits address most cases effectively. Persistent bleeding, painful thrombosis, or significant prolapse warrant professional evaluation.

If you’re experiencing rectal bleeding, perianal pain, or prolapsing tissue, consult a colorectal surgeon for comprehensive evaluation and treatment options.