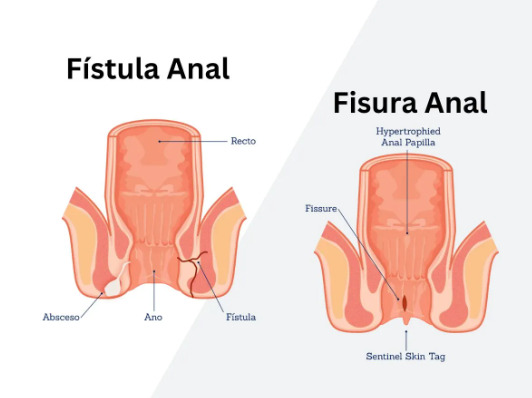

Did you know that some anal fistulas have only one opening instead of the typical two? A blind anal fistula presents diagnostic and treatment challenges compared to conventional fistulas. Unlike complete fistulas that connect two surfaces with openings at both ends, blind anal fistulas have only one opening—either internal at the anal canal or external on the perianal skin. This incomplete tract formation occurs when infection or inflammation creates a pathway that fails to establish full communication between the anal canal and external skin surface.

The condition develops through similar mechanisms as complete fistulas, typically originating from infected anal glands located between the internal and external anal sphincters. When these cryptoglandular infections spread through tissue planes, they may encounter anatomical barriers or undergo partial healing, resulting in an incomplete tract. Internal blind fistulas open only into the anal canal without reaching the skin, while external blind fistulas manifest as persistent draining sinuses on the perianal skin without an identifiable internal opening.

Types and Classification

Internal Blind Fistula

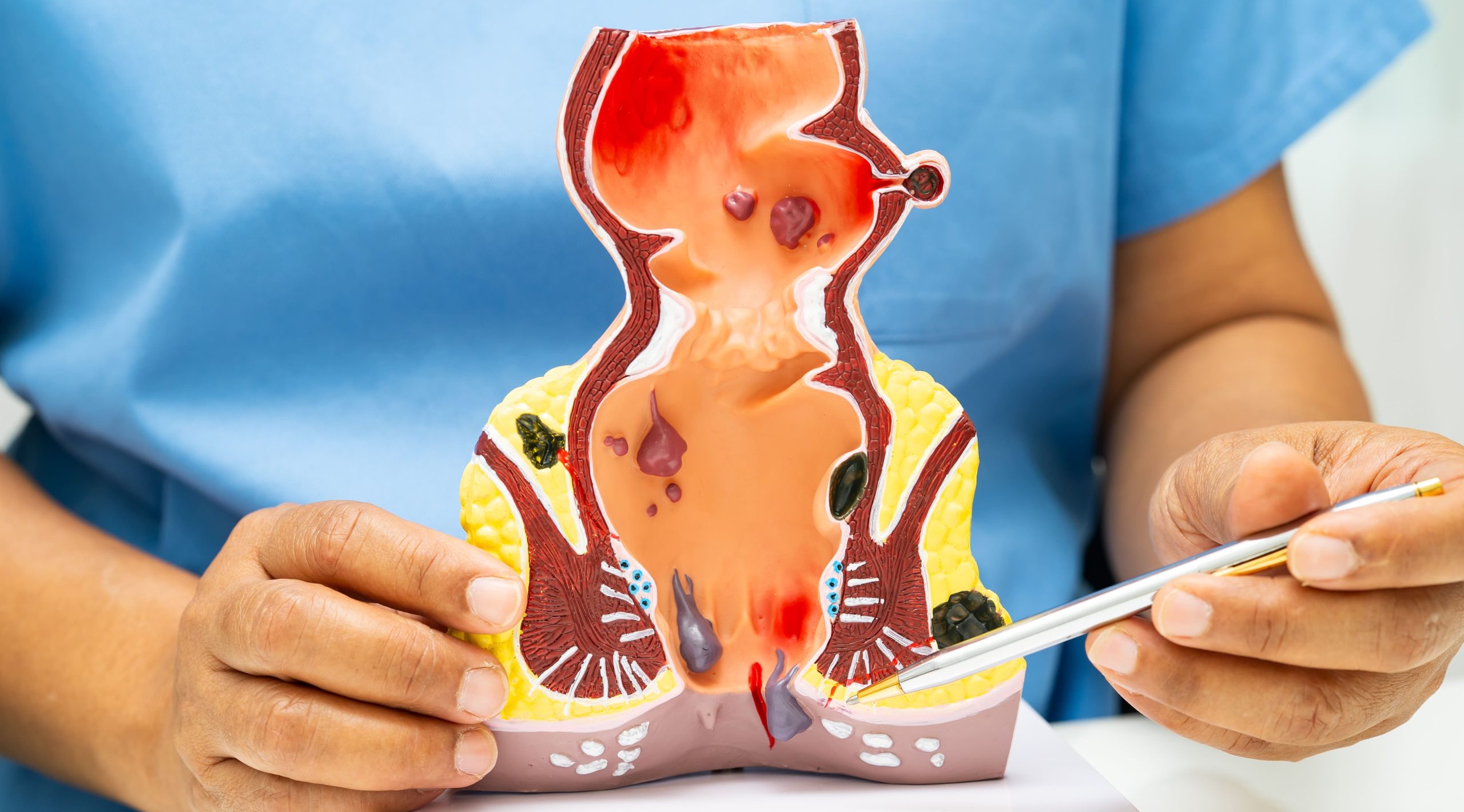

Internal blind fistulas originate from the anal canal but terminate within perianal tissues without creating an external opening. The tract extends from an infected crypt through the internal sphincter into the intersphincteric space, where it may end blindly or form a cavity. Patients experience deep anal pain, particularly during defecation, along with intermittent discharge of pus or blood through the anus. The absence of external drainage often leads to recurrent abscess formation as infected material accumulates within the closed tract.

Digital rectal examination reveals induration or a palpable cord-like structure extending from the dentate line. Anoscopy may identify the internal opening as a small pit or granulation tissue at the crypt level. These fistulas frequently follow the path of least resistance through the intersphincteric plane, though some may penetrate partway through the external sphincter before terminating.

External Blind Fistula

External blind fistulas present as chronic draining sinuses on the perianal skin without demonstrable communication to the anal canal. The tract extends inward toward the anal canal but fails to penetrate completely through the sphincter complex. These often result from incompletely drained perianal abscesses or previous surgical interventions where the internal opening sealed while external drainage persisted.

The external opening typically appears as a small papilla or dimple with surrounding induration, located close to the anal verge. Gentle probing reveals a tract extending toward the midline, though the internal terminus cannot be identified. Intermittent drainage alternates with periods of apparent healing, only to recur when debris accumulates within the tract. Secondary openings may develop if infection spreads laterally through tissue planes.

Horseshoe Blind Fistula

Horseshoe configurations represent complex blind fistulas where the primary tract extends circumferentially around the anus in the ischiorectal or intersphincteric space. The posterior midline serves as the usual origin, with extensions passing laterally on one or both sides without establishing secondary internal openings. This creates a U-shaped configuration that may remain blind internally, externally, or at multiple points along its course.

These fistulas produce diffuse perianal discomfort with tenderness extending beyond the location of visible openings. Induration follows the horseshoe path, often palpable as a cord-like thickening in the posterior perianal region. Multiple external openings may be present while the internal opening remains absent or sealed, complicating surgical planning.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Blind anal fistulas manifest through persistent perianal symptoms that differ from complete fistulas due to impaired drainage. Pain intensity fluctuates with tract distension—minimal when draining freely but severe when the opening becomes blocked. The trapped infectious material creates pressure within tissues, producing throbbing discomfort that intensifies until spontaneous drainage occurs or intervention provides relief.

Discharge characteristics vary with tract anatomy and drainage efficiency. External blind fistulas produce visible perianal drainage—serous, purulent, or serosanguineous—that stains undergarments. Internal blind fistulas discharge into the anal canal, causing anal wetness, pruritus, and occasional blood streaking on toilet tissue. The discharge volume correlates with tract activity, increasing during infection exacerbations.

💡 Did You Know?

Blind anal fistulas may temporarily seal at their opening, creating a closed cavity that mimics an abscess. This pseudo-healing explains why some patients experience cyclical symptoms with apparent resolution followed by sudden recurrence.

Perianal skin changes develop from chronic inflammation and repeated infection cycles. Induration extends along the tract path, creating palpable subcutaneous cords. Skin discoloration ranges from erythema during acute inflammation to hyperpigmentation in chronic cases. Excoriation and maceration occur from persistent moisture, particularly with external blind fistulas producing continuous drainage.

Constitutional symptoms accompany infection exacerbations. Low-grade fever develops when pus accumulates within the blind tract. Malaise and focal lymphadenopathy indicate active infection requiring evaluation. These systemic signs differentiate active infection from chronic inflammation, guiding treatment timing.

Diagnostic Approaches

Physical Examination Techniques

Systematic examination identifies blind anal fistula characteristics while mapping tract anatomy. Inspection reveals external openings, skin changes, and drainage patterns. The opening location relative to the anal verge suggests tract direction—anterior openings typically follow straight paths while posterior openings may have complex courses. Goodsall’s rule provides general guidance, though blind fistulas may deviate from predicted patterns.

Digital examination assesses sphincter integrity and identifies induration suggesting tract location. The examining finger palpates circumferentially, noting areas of thickening or tenderness. Internal blind fistulas may produce a palpable nodule or cord at the dentate line level. Bidigital palpation between the examining finger and external thumb defines tract depth relative to sphincter muscles.

Anoscopy visualizes the anal canal for internal openings, though these remain absent in external blind fistulas. Granulation tissue, crypt hypertrophy, or focal induration suggests the site of an internal blind fistula. Gentle probing from identified openings determines tract direction and depth, though forced probing risks creating false passages.

Imaging Studies

MRI provides optimal soft tissue visualization for mapping blind fistula anatomy. T2-weighted sequences with fat suppression highlight fluid-filled tracts as hyperintense signals against surrounding tissue. The blind end appears as tract termination without connection to another epithelial surface. Gadolinium enhancement distinguishes active inflammation from fibrosis, guiding surgical timing.

Endoanal ultrasound offers real-time evaluation using high-frequency transducers. Fistula tracts appear as hypoechoic bands traversing normal tissue planes. The blind terminus shows as tract ending without breakthrough to opposing surfaces. Three-dimensional reconstruction helps visualize complex tract relationships to sphincter muscles.

Fistulography involves injecting contrast through external openings to outline tract anatomy. Blind fistulas show contrast accumulation at the terminus without passage to another surface. This technique identifies tract extensions and secondary branches, though inflammation may prevent complete filling. Hydrogen peroxide enhancement during ultrasound improves tract visualization through microbubble formation.

Examination Under Anesthesia

Surgical evaluation under anesthesia permits thorough assessment without patient discomfort. Muscle relaxation facilitates complete examination of the anorectum and perianal tissues. Systematic probing from identified openings maps tract extent while avoiding false passage creation.

The internal opening search employs multiple techniques when not readily apparent. Injection of methylene blue or hydrogen peroxide through external openings may reveal previously unidentified internal communications. Gentle curettage of the tract sometimes exposes an internal opening obscured by granulation tissue. The absence of dye emergence after adequate injection confirms the blind nature.

⚠️ Important Note

Vigorous probing or excessive force during examination under anesthesia may convert a blind fistula to a complete fistula by creating iatrogenic communications. Gentle technique preserves anatomical relationships for accurate assessment.

Treatment Options

Conservative Management

Some blind anal fistulas respond to non-operative treatment when infection remains controlled and symptoms tolerable. Sitz baths three times daily promote drainage and reduce inflammation through warm water immersion. The heat increases local blood flow while the moisture softens debris blocking tract openings.

Antibiotic therapy targets specific organisms when culture data exists, though empirical coverage for mixed aerobic-anaerobic flora often suffices. Metronidazole combined with ciprofloxacin provides broad spectrum coverage for typical perianal pathogens. Treatment duration extends several weeks for acute exacerbations, though chronic suppression may continue longer in some cases.

Local wound care maintains drainage and prevents premature closure of external openings. Daily irrigation with saline removes debris accumulating within accessible tracts. Alginate or iodoform gauze wicking keeps external openings patent while absorbing discharge. Barrier creams protect perianal skin from moisture-related maceration.

Surgical Interventions

Fistulotomy is a treatment for superficial blind fistulas involving minimal sphincter muscle. The tract is unroofed from the opening to its blind terminus, converting it to an open wound that heals by secondary intention. Complete curettage removes granulation tissue and epithelial lining to prevent recurrence. The wound edges are marsupialized to promote healing from the base upward.

Fistulectomy excises the entire tract including surrounding inflammatory tissue. This approach suits blind fistulas with extensive induration or suspected malignancy. The resulting defect requires careful reconstruction to prevent deformity. Primary closure accelerates healing in some cases, though most wounds heal secondarily.

Seton placement manages high blind fistulas involving significant sphincter muscle. The seton passes from the opening through the tract, exiting through a created counter-opening at the blind end. Cutting setons gradually divide muscle over weeks, allowing fibrosis to maintain continence. Draining setons control infection while preserving sphincter integrity for staged procedures.

Procedures for Complex Cases

Advancement flaps address high internal blind fistulas while preserving sphincter function. The procedure mobilizes healthy anorectal mucosa and internal sphincter to cover the internal opening after tract excision. The flap blood supply from proximal tissue ensures viability. The external portion heals secondarily or receives simultaneous excision depending on tract configuration.

LIFT (Ligation of Intersphincteric Fistula Tract) procedure suits blind fistulas confined to intersphincteric space. The approach identifies and divides the tract through an intersphincteric incision, removing infected tissue while preserving sphincter continuity. The internal opening is closed with absorbable suture while the distal tract undergoes curettage.

Fibrin glue or collagen plugs offer sphincter-sparing alternatives for some blind fistulas. After thorough curettage, the biomaterial fills the tract to promote healing. The blind nature eliminates concerns about internal opening closure failure. Success depends on adequate tract preparation and absence of active infection.

Complications and Prognosis

Untreated blind anal fistulas risk several complications requiring intervention. Abscess formation occurs when drainage becomes obstructed, creating a painful fluctuant mass requiring incision and drainage. The abscess may be superficial and easily accessible or deep within ischiorectal or supralevator spaces, necessitating examination under anesthesia for adequate drainage. Systemic infection develops if treatment delays, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Complex branching patterns emerge when infection spreads through tissue planes from the primary blind tract. Secondary tracts extend laterally or circumferentially, creating multiple external openings while the original blind configuration persists. These extensions complicate surgical management and increase recurrence risk. Each branch requires individual assessment and treatment to achieve complete healing.

Malignant transformation, though rare, occurs in chronic fistulas present for many years. Adenocarcinoma arising from the tract epithelium presents as increasing induration, bleeding, or pain changes. Biopsy of suspicious tissue confirms diagnosis. The transformation risk increases with disease duration, emphasizing the importance of treatment for persistent fistulas.

Treatment outcomes vary with blind fistula anatomy and chosen intervention. Simple low blind fistulas treated with fistulotomy achieve good healing rates within 6-12 weeks. Complex or high blind fistulas requiring sphincter-preserving procedures show variable success rates, with some patients requiring multiple interventions. Recurrence manifests as persistent drainage or pain at the original site, though new blind fistulas may develop from untreated secondary tracts.

Post-Treatment Care

Wound management after blind fistula surgery focuses on promoting healing while preventing premature closure. Daily wound irrigation removes debris and necrotic tissue that impedes granulation. Saline or dilute antiseptic solutions provide adequate cleansing without damaging healthy tissue. The irrigation stream should reach the wound base, particularly in deep cavities from fistulectomy.

✅ Quick Tip

Position changes during sitz baths ensure water circulation reaches all wound surfaces. Gentle spreading of the buttocks allows warm water to contact deeper portions of the healing tract.

Dressing selection depends on wound characteristics and drainage volume. Alginate dressings absorb moderate to heavy exudate while maintaining moist wound environment. Hydrofiber dressings offer similar absorption with less frequent changes. Silver-impregnated dressings provide antimicrobial activity when infection risk remains. The dressing should loosely fill dead space without tight packing that impedes drainage.

Activity modification balances mobility with wound protection. Walking promotes circulation and prevents venous stasis, though prolonged sitting increases perianal pressure. Gradual return to normal activities occurs over several weeks for simple procedures or longer for complex reconstructions. Heavy lifting and straining should be avoided until complete healing occurs.

Pain management combines pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Scheduled paracetamol provides baseline analgesia while NSAIDs reduce inflammation when not contraindicated. Topical anesthetics offer temporary relief for dressing changes. Stool softeners prevent straining that exacerbates pain during defecation.

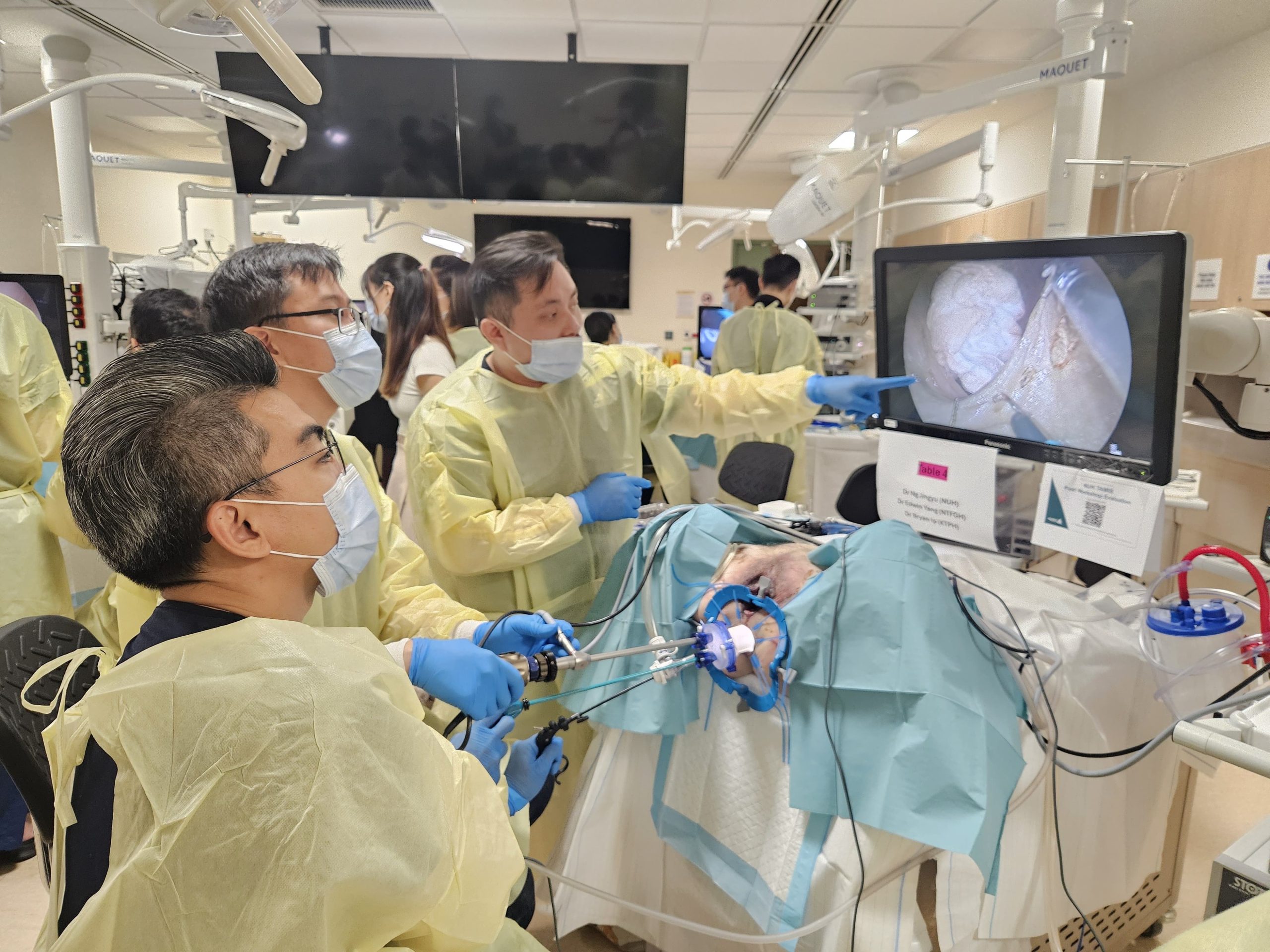

What Our Colorectal Surgeon Says

Blind anal fistulas often perplex both patients and physicians due to their incomplete anatomy and variable presentation. The absence of a complete tract creates diagnostic uncertainty—many patients undergo multiple examinations before the blind nature becomes apparent. Current imaging, particularly MRI, has transformed our ability to map these lesions accurately before surgery.

The surgical approach must balance complete disease eradication with functional preservation. While fistulotomy offers a high cure rate, the amount of sphincter muscle involved often necessitates staged or sphincter-sparing procedures. Complex blind fistulas may require multiple operations to achieve healing.

The timing of intervention requires careful consideration. Operating during acute inflammation increases technical difficulty and complication risk. Allowing inflammation to settle with preliminary drainage or seton placement often simplifies definitive repair. However, excessive delay risks tract extension or secondary opening development.

Putting This Into Practice

- Monitor drainage patterns from existing openings, noting changes in volume, color, or odor that suggest infection exacerbation or tract extension

- Maintain meticulous perianal hygiene through gentle cleansing after bowel movements and regular sitz baths to reduce bacterial load and promote drainage

- Document symptom progression including pain location, intensity changes, and relationship to bowel movements to help your surgeon map tract anatomy

- Protect perianal skin with moisture barriers when experiencing continuous drainage, reapplying after each cleansing to prevent maceration

- Schedule evaluation for new symptoms such as fever, increasing pain, or new areas of swelling that may indicate abscess formation

When to Seek Professional Help

- Sudden severe pain with perianal swelling suggesting abscess formation

- Fever above 38°C with perianal symptoms

- New drainage sites developing near the anus

- Increasing induration or firm areas around existing openings

- Bleeding beyond minor spotting

- Failure of symptoms to improve after several weeks of conservative treatment

- Difficulty controlling bowel movements or gas

- Persistent drainage despite previous surgical treatment

Commonly Asked Questions

Can a blind anal fistula heal without surgery?

Some superficial external blind fistulas may heal with conservative management including antibiotics and local wound care. However, most blind fistulas require surgical intervention for treatment. Internal blind fistulas rarely heal spontaneously due to continuous contamination from the anal canal. The healing potential depends on tract depth, sphincter involvement, and underlying conditions affecting wound healing.

How long does recovery take after blind fistula surgery?

Recovery duration varies with surgical extent and technique. Simple fistulotomy wounds typically heal within 6-8 weeks. Complex procedures involving flaps or sphincter reconstruction require 10-12 weeks for complete healing. Return to normal activities occurs gradually, with desk work resuming within 1-2 weeks and strenuous activity after 4-6 weeks. Individual healing rates vary based on overall health and wound care compliance.

Why did my fistula become blind instead of complete?

Blind fistulas develop when normal tract formation becomes interrupted. Partial treatment of an abscess may leave residual infection that forms an incomplete tract. Natural healing processes sometimes seal one opening while the other persists. Anatomical barriers like fascial planes may prevent complete tract formation. Some medications or immune conditions affect tissue response to infection, promoting blind rather than complete fistula development.

Can a blind fistula convert to a complete fistula?

Blind fistulas may spontaneously develop complete communication through continued inflammation and tissue breakdown. External blind fistulas may eventually penetrate remaining tissue to reach the anal canal. Internal blind fistulas may erode through perianal skin. Surgical manipulation during examination or treatment occasionally creates communications converting blind to complete configuration. This conversion doesn’t necessarily worsen prognosis but alters surgical planning.

What happens if a blind anal fistula is left untreated?

Untreated blind fistulas typically persist with chronic symptoms rather than spontaneous resolution. Repeated infection cycles cause progressive tissue damage and tract extension. Abscess formation requires emergency drainage. Quality of life deteriorates from persistent pain, drainage, and activity limitations. Rare complications include systemic infection, complex branching patterns, and malignant transformation in longstanding disease.

Conclusion

Blind anal fistulas require specialized diagnosis and treatment approaches that differ from complete fistulas. Early recognition through proper examination and imaging prevents complications such as abscess formation and tract extension. Treatment success depends on accurate tract mapping and selection of appropriate surgical techniques that balance healing with sphincter preservation.

If you are experiencing persistent perianal drainage, recurring abscesses, or ongoing anal discomfort, consultation with a MOH-accredited colorectal surgeon can provide accurate diagnosis and specialized treatment for your condition.