Introduction

Could laser technology offer a solution for anal fistulas that preserves continence while achieving effective healing? Laser treatment, specifically Fistula Laser Closure (FiLaC), uses controlled thermal energy delivered through a radial-emitting laser fiber to seal the fistula tract. This minimally invasive technique contrasts with traditional fistulotomy, which involves cutting through tissue and sphincter muscles, potentially affecting continence. The FiLaC procedure targets the fistula tract’s epithelial lining while preserving surrounding healthy tissue, making it suitable for complex or high fistulas where conventional surgery carries greater risks. Colorectal surgeons determine treatment suitability based on fistula anatomy, previous surgical history, and sphincter involvement assessed through MRI or endoanal ultrasound.

Understanding Anal Fistulas and Treatment Options

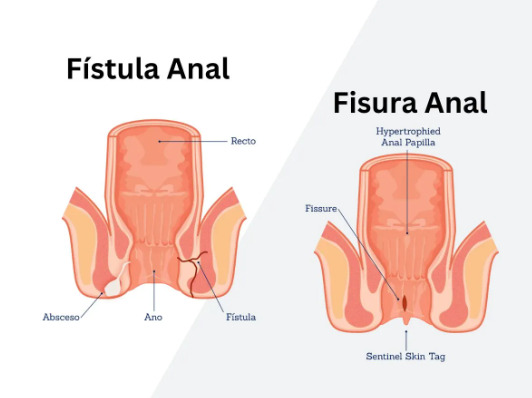

Anal fistulas develop when infected anal glands create tunnels through surrounding tissue, establishing drainage pathways to the skin surface. The internal opening typically originates at the dentate line where anal glands empty, while external openings appear as small holes near the anus that discharge pus or blood-stained fluid.

Fistula classification depends on the tract’s relationship to sphincter muscles. Simple fistulas pass through minimal sphincter muscle, while complex fistulas involve significant sphincter portions, cross multiple muscle layers, or branch into multiple tracts. Transphincteric fistulas traverse both internal and external sphincters, intersphincteric fistulas track between these muscle layers, and suprasphincteric fistulas loop above the puborectalis muscle before descending through the ischiorectal fossa.

Treatment selection considers sphincter involvement, previous interventions, and continence preservation requirements. Fistulotomy remains suitable for low, simple fistulas involving minimal external sphincter. Seton placement manages complex fistulas through staged procedures, using surgical thread to gradually cut through or promote fibrosis. Advancement flaps cover the internal opening with healthy tissue, while LIFT (Ligation of Intersphincteric Fistula Tract) procedures ligate the tract between sphincter muscles.

Anal fistula laser treatment is a sphincter-sparing alternative that addresses limitations of conventional techniques. The procedure suits patients with high transphincteric fistulas, anterior fistulas in women, recurrent fistulas after previous surgery, and those requiring sphincter preservation due to prior obstetric injury or inflammatory bowel disease.

The FiLaC Procedure

FiLaC employs a diode laser operating at 1470nm wavelength, delivering 12-15 watts of energy through a radial-emitting fiber. The wavelength targets water molecules in tissue, creating controlled thermal ablation at 100-120°C that destroys the fistula tract’s epithelial lining while stimulating collagen remodeling.

Pre-procedure preparation includes MRI or endoanal ultrasound to map fistula anatomy, identifying internal and external openings, secondary tracts, and associated abscesses. Mechanical bowel preparation occurs the night before surgery, with phosphate enemas administered morning of the procedure. Prophylactic antibiotics, typically metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, may begin 24 hours before surgery as determined by the healthcare team.

The surgical technique begins with examination under anesthesia to confirm fistula anatomy. A fistula probe navigates from external to internal opening, establishing tract pathway. The laser fiber, protected by a catheter sheath, follows the probe’s path. Surgeons activate the laser while withdrawing the fiber at 1mm per second, delivering circumferential energy that ablates the tract lining. Total energy delivery ranges from 200-500 joules depending on tract length, typically requiring 3-5 minutes of laser activation.

Surgeons may combine FiLaC with ancillary procedures to enhance healing. Curettage removes granulation tissue and debris before laser application. Internal opening closure using absorbable sutures prevents contamination from the anal canal. Some surgeons inject platelet-rich plasma or fibrin glue into the ablated tract to promote healing. Drainage seton placement before FiLaC ensures infection resolution in cases with active sepsis.

Post-procedure tissue changes include immediate coagulation necrosis of the epithelial lining, followed by inflammatory response and granulation tissue formation within 7-14 days. Fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition gradually obliterate the tract over 6-12 weeks, with complete healing typically evident by 3 months on follow-up imaging.

Recovery and Aftercare

Immediate post-procedure care focuses on pain management and wound hygiene. Patients receive multimodal analgesia combining paracetamol, NSAIDs, and short-course opioids for breakthrough pain. Local anesthetic infiltration provides additional comfort during the first 24-48 hours. Stool softeners prevent straining, while dietary fiber supplements maintain regular bowel movements.

The external opening requires daily cleaning with saline solution, followed by gentle pat-drying. Sitz baths three times daily for 10-15 minutes promote hygiene and comfort. Topical metronidazole gel applied to the external opening reduces bacterial load. Absorbent pads manage drainage, which gradually decreases from serosanguinous to serous before ceasing completely.

Recovery timeline follows predictable patterns. Days 1-3 involve moderate discomfort managed with oral analgesics, with patients typically resuming light activities. Week 1 sees drainage reduction and improved comfort, allowing return to desk work. Weeks 2-4 bring continued healing with minimal drainage, permitting gradual activity increase. By weeks 6-8, complete tract closure occurs in successful cases, with full activities including exercise resumed. Three-month follow-up confirms healing through clinical examination and imaging if indicated.

⚠️ Important Note

Persistent drainage beyond 8 weeks, increasing pain after initial improvement, or new swelling suggests incomplete healing requiring reassessment by your colorectal surgeon.

Complications remain uncommon but require prompt recognition. Incomplete fistula closure manifests as continued drainage despite initial improvement. Tract infection presents with increased pain, purulent discharge, and fever. Rare bleeding occurs from granulation tissue, typically self-limiting. Continence is typically preserved, though temporary urgency may occur during initial healing.

Activity modifications during recovery include:

- Avoiding heavy lifting exceeding 10kg for 4 weeks

- Postponing swimming until external opening closes

- Limiting prolonged sitting during the first week

Sexual activity can resume when comfortable, typically after 2-3 weeks.

Success Factors and Outcomes

Healing rates after anal fistula laser treatment vary based on fistula characteristics and patient factors. Primary healing occurs when the tract completely obliterates without recurrence. Technical success means absence of symptoms and clinical evidence of closure. Functional success includes healing with preserved continence and quality of life improvement.

Favorable prognostic factors include:

- Tract length under 4cm

- Single unbranched tract anatomy

- Absence of active infection

- Previous drainage seton placement

Patient factors influencing outcomes include:

- Adequate nutrition status

- Absence of immunosuppression

- Non-smoking status

- Controlled diabetes

Complex fistulas present unique challenges requiring modified approaches. Horseshoe fistulas need multiple laser fiber insertions to address all extensions. Rectovaginal fistulas benefit from combined vaginal advancement flap. Previous failed surgery necessitates careful tract identification and complete epithelial ablation. Crohn’s disease-related fistulas require optimized medical therapy before attempting FiLaC.

Long-term follow-up extends beyond initial healing confirmation. Three-month assessment includes clinical examination and patient-reported outcomes. Six-month evaluation confirms sustained closure and continence preservation. Annual review for 2 years monitors for late recurrence. MRI or endoanal ultrasound at 6 months provides objective healing documentation in complex cases.

When to Seek Professional Help

- Persistent anal discharge lasting more than two weeks

- Recurrent perianal abscesses requiring drainage

- Pain or swelling around previous abscess drainage sites

- Blood-stained discharge from openings near the anus

- Skin irritation from continuous drainage

- Multiple drainage points around the anal area

- Cyclical symptoms of swelling, drainage, and temporary improvement

- Previous fistula surgery with symptom recurrence

- Inflammatory bowel disease with new perianal symptoms

Commonly Asked Questions

How does laser treatment compare to traditional fistulotomy for healing rates?

Simple fistulotomy achieves healing rates but requires cutting through sphincter muscle, risking continence. FiLaC preserves sphincter integrity with healing rates that vary depending on fistula complexity, making it an option when continence preservation is important.

Can laser treatment be repeated if the first attempt fails?

Repeat FiLaC remains feasible after initial failure, particularly if partial healing occurred. The second procedure often combines laser treatment with additional techniques like advancement flap or internal opening closure. Timing typically waits 3-6 months after the first attempt to allow inflammation resolution.

What determines whether I’m suitable for laser treatment versus other options?

Suitability depends on fistula anatomy revealed by MRI, sphincter involvement degree, previous anal surgery history, baseline continence status, and underlying conditions like Crohn’s disease. High transphincteric fistulas and those in patients requiring sphincter preservation may benefit from laser treatment.

How long before I know if the laser treatment has worked?

Initial healing assessment occurs at 6-8 weeks when drainage should cease and the external opening close. Complete healing confirmation requires 3 months, as some tracts continue maturing during this period. Persistent minimal drainage at 6 weeks doesn’t necessarily indicate failure if progressive improvement continues.

What happens if laser treatment doesn’t completely close the fistula?

Incomplete closure options include repeat FiLaC with technical modifications, conversion to advancement flap procedure, long-term seton management for symptom control, or staged fistulotomy in selected cases. Your colorectal surgeon determines the appropriate strategy based on residual anatomy and previous response.

Conclusion

FiLaC offers effective fistula healing while preserving sphincter function, particularly for complex cases. Success depends on appropriate patient selection based on fistula anatomy and proper post-procedure care. Consider this option when experiencing persistent drainage or requiring sphincter preservation.

If you’re experiencing persistent anal drainage, recurrent perianal infections, or symptoms around previous abscess sites, a MOH-accredited colorectal surgeon can evaluate whether anal fistula laser treatment is appropriate for your specific condition.