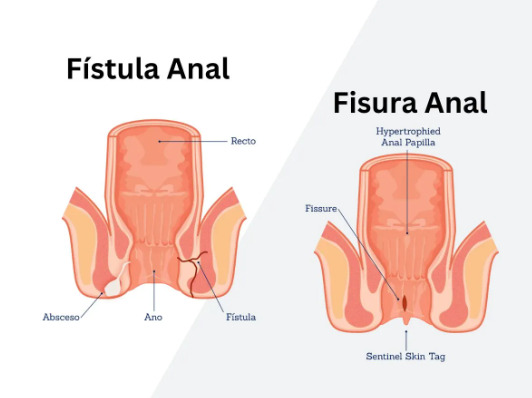

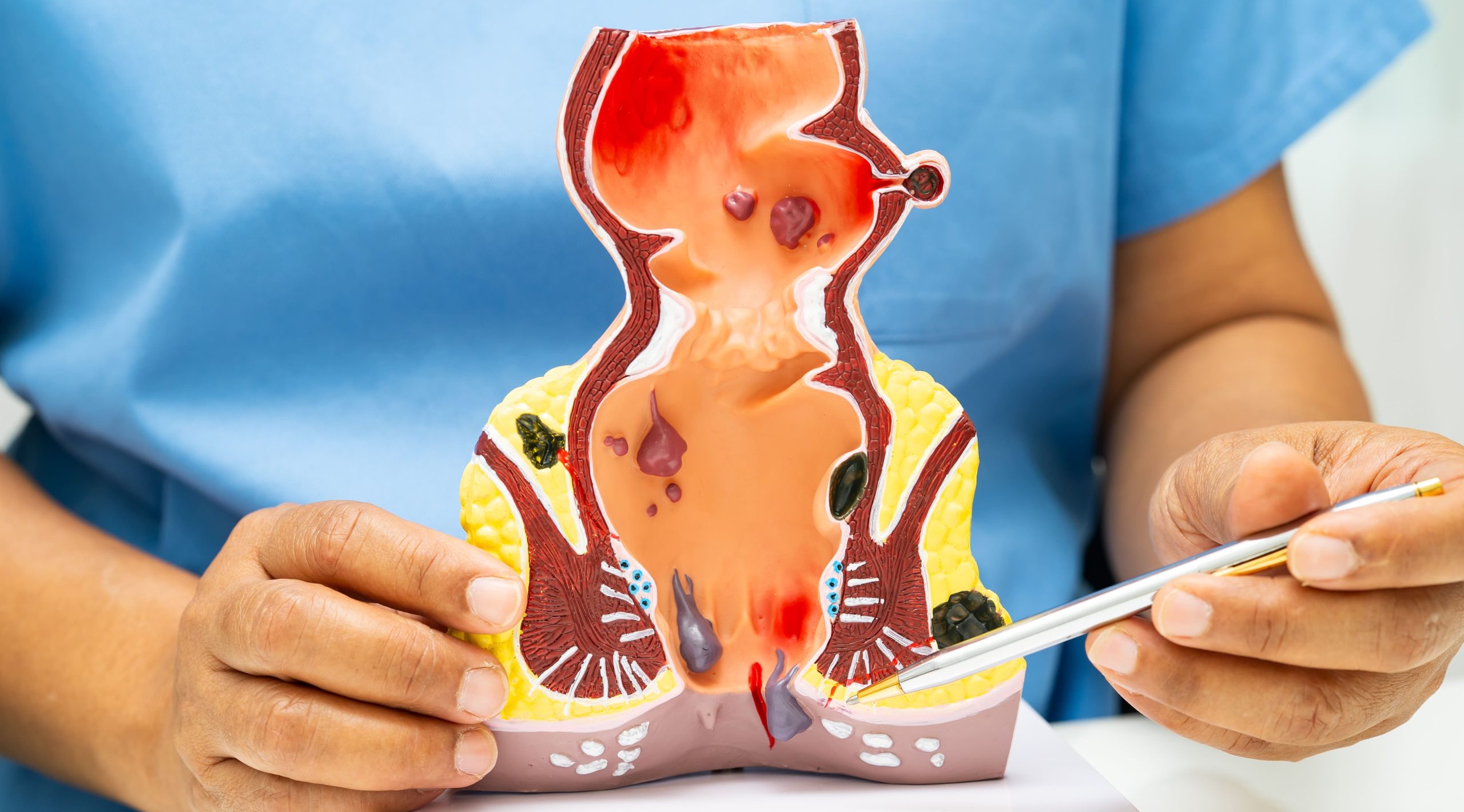

Do you know the difference between a tear in your anal canal and an abnormal tunnel connecting it to your skin? An anal fissure is a linear tear in the anal canal lining that causes sharp pain during bowel movements and bright red bleeding on toilet paper. An anal fistula is an abnormal tunnel connecting the anal canal to the skin near the anus, typically presenting with persistent drainage of pus or fluid and a visible external opening. While both conditions affect the anal region and cause discomfort, their underlying pathology, symptoms, and treatment approaches differ significantly.

Fissures develop from trauma to the anal canal – usually from passing hard stools, chronic diarrhea, or excessive straining. The tear occurs in the anoderm, the specialized skin lining the lower anal canal rich with pain nerve endings. Fistulas form when an anal gland becomes infected, creating an abscess that eventually burrows through surrounding tissue to create a drainage pathway. This fundamental difference in origin determines how each condition progresses and responds to treatment.

Fissures often heal with conservative management, while fistulas typically require surgical intervention. Proper identification helps ensure appropriate treatment and symptom management.

Anatomy and Development

Anal Fissures

The anal canal measures approximately 4 centimeters in length, extending from the anorectal junction to the anal verge. Fissures typically occur in the posterior midline where blood supply is relatively poor. The tear extends through the anoderm but not deeper into the muscle layers initially.

Acute fissures appear as fresh tears with clean edges, similar to a paper cut. Without healing within 6-8 weeks, chronic fissures develop characteristic features: raised edges called sentinel piles at the external end, hypertrophied anal papillae at the internal end, and exposed internal sphincter muscle fibers at the base. The internal anal sphincter often goes into spasm, reducing blood flow and perpetuating the cycle of poor healing.

Secondary fissures occurring in atypical locations (lateral or multiple sites) suggest underlying conditions like Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, HIV, or malignancy. These require different management approaches and thorough investigation.

Anal Fistulas

Fistulas originate from cryptoglandular infection in anal glands located at the dentate line. These glands normally secrete mucus for lubrication but can become blocked, leading to bacterial overgrowth and abscess formation. The abscess seeks the path of least resistance, creating a tract through surrounding tissues.

Parks classification categorizes fistulas based on their relationship to the sphincter muscles:

- Intersphincteric: Track runs between internal and external sphincters

- Transsphincteric: Track crosses through external sphincter

- Suprasphincteric: Track loops over external sphincter

- Extrasphincteric: Track bypasses sphincter complex entirely

Complex fistulas involve multiple tracts, horseshoe extensions, or high involvement of sphincter muscles. The internal opening typically follows Goodsall’s rule: fistulas with external openings posterior to the transverse anal line usually have internal openings in the posterior midline, while anterior external openings tend to track radially to the nearest crypt.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

Anal Fissure Symptoms

Sharp, cutting pain during defecation characterizes anal fissures. Patients often describe it as “passing broken glass” or “razor blades.” The pain peaks during bowel movements and may persist for hours afterward due to sphincter spasm. This creates a fear-pain-constipation cycle where patients avoid defecation, leading to harder stools that worsen the fissure.

Bright red blood appears on toilet paper or coating the stool surface. The bleeding is minimal – rarely enough to drip into the toilet bowl. Some patients notice a small skin tag (sentinel pile) at the anal opening, which they may mistake for a hemorrhoid.

Chronic fissures cause intermittent symptoms with periods of improvement followed by re-tearing. The sphincter spasm creates a constant aching or burning sensation between bowel movements. Pruritus ani (anal itching) develops from chronic inflammation and moisture.

Anal Fistula Symptoms

Persistent perianal drainage defines fistula presentation. The discharge varies from clear fluid to thick pus, often blood-tinged, requiring frequent pad changes. The drainage increases with bowel movements as stool particles enter the tract. Many patients report a foul odor despite meticulous hygiene.

A palpable cord-like structure extends from the external opening toward the anus. The external opening appears as a small hole or raised area with granulation tissue, sometimes multiple openings exist. Intermittent swelling occurs when the tract becomes temporarily blocked, causing pain until spontaneous drainage resumes.

Systemic symptoms remain uncommon unless active infection develops. Recurrent perianal abscesses in the same location suggest underlying fistula formation. The cyclical pattern of abscess-drainage-temporary healing-recurrence continues until treatment addresses the fistula tract.

Diagnosis Methods

Physical Examination

Digital rectal examination reveals distinct findings for each condition. Fissures cause severe tenderness and sphincter spasm, often preventing complete examination. The tear is sometimes visible by gently spreading the buttocks, appearing as a longitudinal split in the anoderm. Chronic fissures show the triad of sentinel pile, exposed sphincter fibers, and hypertrophied papilla.

Fistula examination identifies the external opening location and attempts to determine the tract direction through gentle probing. Expressing the tract may produce drainage from the external opening. Anoscopy helps locate the internal opening, though this isn’t always visible. The examining finger may palpate an indurated cord representing the fistula tract.

Imaging Studies

Fissures rarely require imaging unless atypical features suggest underlying pathology. Endoscopy evaluates for inflammatory bowel disease when multiple fissures, lateral location, or poor healing occurs.

Fistula imaging determines tract anatomy before surgical planning:

- MRI pelvis: Standard imaging for complex fistulas, providing detailed soft tissue visualization without radiation

- Endoanal ultrasound: Identifies tract location relative to sphincters using a rotating probe

- Fistulography: Contrast injection into external opening – limited accuracy due to poor filling of secondary tracts

Examination under anesthesia allows thorough assessment when office examination proves too uncomfortable or inconclusive. Surgeons can probe the tract, inject hydrogen peroxide or methylene blue to identify the internal opening, and perform initial drainage procedures.

Treatment Approaches

Conservative Management for Fissures

First-line treatment focuses on stool softening and sphincter relaxation. Fiber supplementation with adequate fluid intake creates bulky, soft stools that pass without trauma. Sitz baths in warm water after bowel movements reduce sphincter spasm and improve blood flow.

Topical medications applied inside the anal canal include:

- Nitroglycerin ointment: Relaxes internal sphincter through nitric oxide pathway

- Diltiazem or nifedipine cream: Calcium channel blockers reducing sphincter pressure

- Lidocaine preparations: Temporary pain relief allowing easier defecation

Treatment duration and healing rates for chronic fissures vary. Headaches from nitroglycerin affect some patients but usually improve with continued use. Botulinum toxin injection into internal sphincter provides an alternative when topical therapy fails, achieving healing in many cases.

Surgical Options

Lateral internal sphincterotomy is a treatment for chronic anal fissures when conservative management is unsuccessful. The procedure divides the lower third of the internal sphincter, eliminating spasm and improving blood flow. Healing occurs in most cases. Minor incontinence to gas affects some patients long-term.

Fistulotomy treats simple, low fistulas by opening the entire tract and allowing healing by secondary intention. The surgeon passes a probe through the tract, then divides all tissue above it. Marsupialization (suturing tract edges to surrounding skin) reduces healing time. Success rates are favorable for intersphincteric and low transsphincteric fistulas.

Complex fistulas require sphincter-preserving techniques:

- Seton placement: Vessel loop or suture through tract allows drainage and fibrosis

- LIFT procedure (Ligation of Intersphincteric Fistula Tract): Divides tract between sphincters

- Advancement flap: Covers internal opening with relocated tissue

- Fibrin glue or fistula plug: Biological materials promoting tract closure

Multiple procedures may be necessary for complex fistulas, with success rates varying depending on fistula characteristics and technique selection.

Recovery and Prognosis

Post-Treatment Care

Fissure surgery recovery involves managing pain during the first week as the surgical site heals. Regular sitz baths, stool softeners, and analgesics control symptoms. Normal activities resume within 1-2 weeks, with complete healing by 6-8 weeks. Maintaining soft stools prevents recurrence.

Fistula surgery recovery depends on procedure complexity. Simple fistulotomy wounds heal within 6-12 weeks with daily dressing changes. Patients perform wound irrigation using a handheld shower or sitz baths. Granulation tissue gradually fills the wound from the base upward. Complex procedures may require restricted activity for several weeks.

Long-term Outcomes

Fissure recurrence is more common with medical treatment compared to sphincterotomy. Recurrent fissures often respond to repeat conservative treatment. Addressing underlying constipation remains important for prevention.

Fistula recurrence varies by type and treatment method. Simple fistulas rarely recur after successful fistulotomy. Complex fistulas have higher recurrence rates, particularly with sphincter-preserving techniques. Crohn’s disease-related fistulas require ongoing medical management alongside surgical intervention, with recurrence common despite treatment.

Complications and Risk Factors

Untreated anal fissures may progress to chronic fissures with permanent anatomical changes. The sentinel pile and hypertrophied papilla persist even after fissure healing. Chronic inflammation occasionally leads to anal stenosis requiring surgical correction.

Untreated fistulas risk recurrent abscess formation and complex tract development. Rare complications include systemic infection and necrotizing fasciitis in immunocompromised patients. Malignant transformation in chronic fistulas occurs but remains rare.

Risk factors for both conditions overlap partially:

- Constipation and straining

- Diarrheal illnesses

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Previous anorectal surgery

- Childbirth trauma (fissures)

- Diabetes and immunosuppression (fistulas)

Commonly Asked Questions

Can an anal fissure turn into a fistula?

No, fissures and fistulas have different origins. Fissures are tears in the anal lining, while fistulas develop from infected anal glands. However, both conditions can coexist in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or following anorectal trauma.

How can I tell the difference between a fissure and fistula at home?

Fissures cause sharp pain primarily during bowel movements with minimal bleeding. Fistulas produce continuous drainage from an opening near the anus with less predictable pain patterns. The presence of persistent discharge strongly suggests a fistula rather than a fissure.

Why does my fistula keep coming back after surgery?

Recurrence typically results from missed secondary tracts, inadequate drainage, or unidentified internal opening during initial surgery. Crohn’s disease increases recurrence risk. MRI evaluation before repeat surgery helps identify missed anatomy.

Can these conditions heal without surgery?

Many acute fissures heal with conservative management within 6-8 weeks. Chronic fissures have lower spontaneous healing rates but may respond to medical therapy. Fistulas rarely heal spontaneously – temporary closure sometimes occurs, but the tract usually reopens without definitive treatment.

When should I see a colorectal surgeon versus trying home treatment?

Seek specialist evaluation for symptoms lasting beyond 6 weeks, recurrent problems, atypical features (multiple fissures, lateral location), or any persistent perianal drainage. Evaluation can help prevent progression and identify conditions requiring different management approaches.

Conclusion

Fissures typically respond to conservative management with stool softening and topical medications, while fistulas require surgical tract elimination. Accurate diagnosis based on symptom patterns—sharp pain with bowel movements versus persistent drainage—determines appropriate treatment selection and outcomes.

If you are experiencing persistent anal pain, bleeding, or drainage from an opening near the anus, consult with a colorectal and general surgeons for accurate diagnosis and treatment.