Introduction

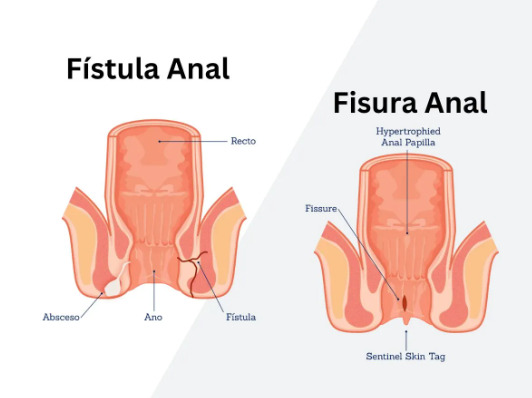

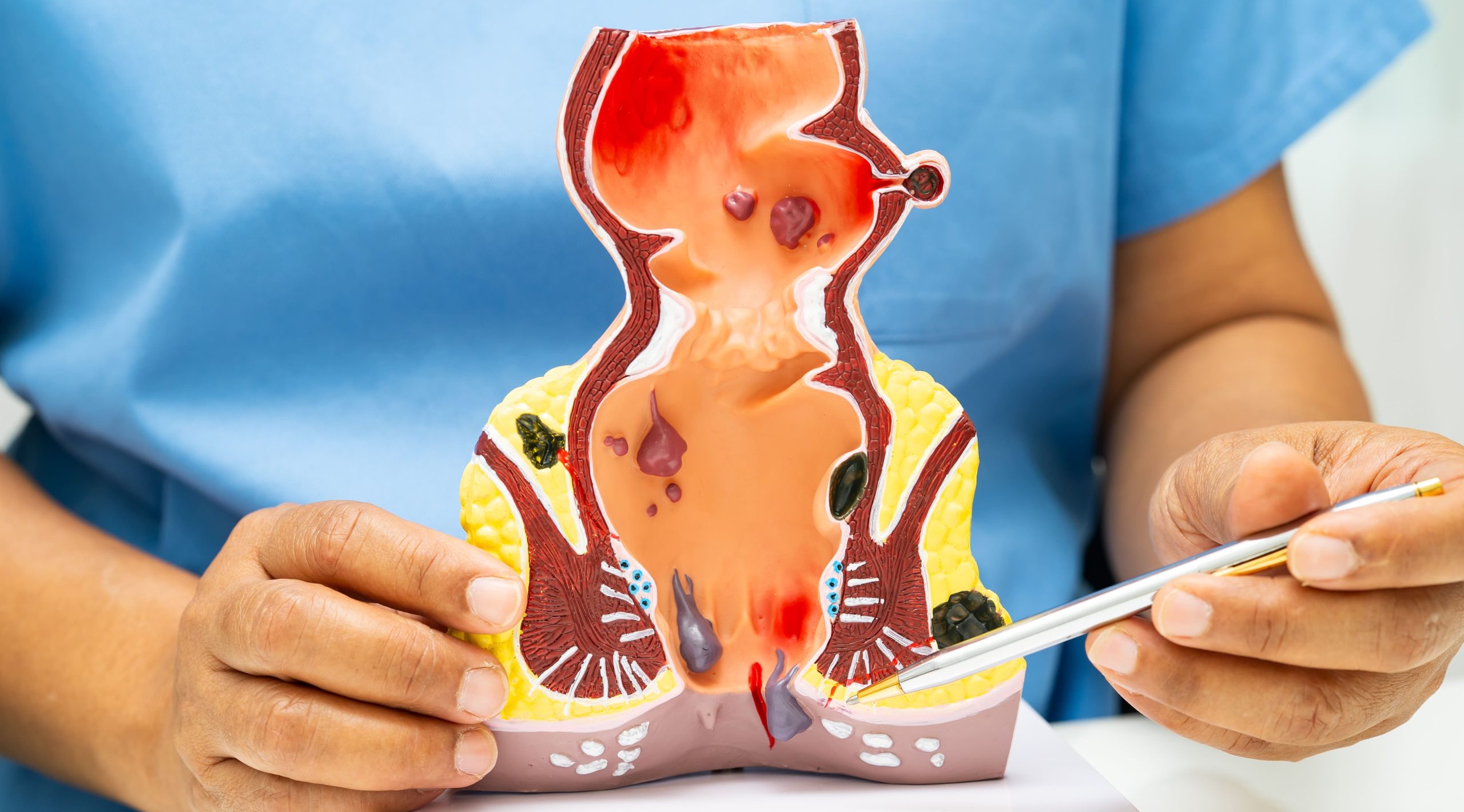

What if a small tunnel beneath your skin could completely disrupt your daily life and refuse to heal naturally? A chronic anal fistula is an abnormal tunnel connecting the anal canal to the skin near the anus, typically developing after an anal abscess fails to heal completely. The condition occurs when infected anal glands create a persistent drainage pathway that does not close naturally after 8-12 weeks. Unlike acute fistulas that may heal with conservative treatment, chronic fistulas have developed epithelialized tracts—meaning the tunnel walls have formed a skin-like lining that prevents spontaneous closure.

The internal opening usually originates from the dentate line inside the anal canal, where anal glands are located, while the external opening appears on the perianal skin. This persistent connection causes continuous or intermittent drainage of pus, blood, or fecal matter through the external opening. The tract may follow a straight path or create complex branching patterns around the anal sphincter muscles, determining both the fistula classification and surgical approach that may be considered for treatment.

Types and Classification of Anal Fistulas

Anal fistulas are classified based on their relationship to the anal sphincter complex, which consists of the internal and external sphincter muscles. This anatomical relationship determines surgical strategy and impacts continence risk.

Intersphincteric fistulas are the most common type, with the tract passing between the internal and external sphincter muscles. These fistulas typically travel downward from the dentate line through the intersphincteric space before opening onto the perianal skin. The tract remains confined between the two muscle layers without penetrating the external sphincter, making surgical treatment manageable with minimal continence risk.

Transsphincteric fistulas traverse both the internal and external sphincter muscles, creating more complex surgical challenges. The tract penetrates through the external sphincter at varying heights—low transsphincteric fistulas cross the lower third of the external sphincter, while high transsphincteric fistulas involve the middle or upper thirds. The amount of sphincter muscle involved correlates with post-surgical continence concerns.

Suprasphincteric fistulas travel upward in the intersphincteric plane before curving over the top of the puborectalis muscle and descending through the ischiorectal fossa to the skin. These complex fistulas often result from cryptoglandular infections that extend superiorly rather than taking the more common downward path.

Extrasphincteric fistulas bypass the sphincter complex entirely, connecting the rectum above the dentate line to the perianal skin. These fistulas usually result from trauma, Crohn’s disease, or pelvic infections rather than typical cryptoglandular disease.

Complex fistulas may feature multiple tracts, horseshoe extensions that wrap around the anus, or secondary branches. These variations often develop when initial surgical attempts fail or when underlying conditions like Crohn’s disease drive ongoing inflammation.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

Chronic anal fistulas produce persistent drainage from the external opening, varying from clear fluid to purulent discharge or blood-tinged material. The drainage typically increases with bowel movements and may have a fecal odor when the internal opening communicates directly with the anal canal. Patients often report needing to wear pads or frequently change underwear due to continuous seepage.

Pain patterns vary depending on the fistula’s activity level and drainage adequacy. Well-draining fistulas may cause minimal discomfort, while those with intermittent blockage create cyclical pain as pressure builds within the tract. The external opening may temporarily seal, leading to abscess reformation with increasing pain, swelling, and fever until spontaneous drainage occurs or surgical intervention provides relief.

Perianal skin irritation develops from chronic moisture exposure and the inflammatory nature of the drainage. The skin surrounding the external opening becomes macerated, red, and excoriated, sometimes developing secondary fungal infections. Patients may notice granulation tissue—pink, fleshy tissue—protruding from the external opening, indicating the body’s attempt at healing.

Bleeding occurs when granulation tissue becomes friable or when stool passage traumatizes the internal opening. While usually minor, persistent bleeding may cause iron deficiency over time. Some patients experience pruritus ani from the chronic moisture and irritation, creating an uncomfortable cycle of itching and scratching that further damages perianal skin.

The psychological impact includes embarrassment from odor and drainage, anxiety about social situations, and frustration with the chronic nature of symptoms. Sexual dysfunction may occur from physical discomfort or psychological distress related to the perianal condition.

Diagnosis and Evaluation

Physical examination remains the cornerstone of fistula diagnosis, with inspection revealing the external opening as a small pit or raised area with surrounding inflammation. Digital rectal examination may identify the internal opening as a palpable nodule or indentation, though high internal openings often escape detection. Gentle probing around the external opening sometimes expresses drainage, confirming the diagnosis.

Anoscopy allows direct visualization of the internal opening at the dentate line, though inflammation and patient discomfort may limit the examination. The procedure helps identify the primary crypt involved and assess for multiple internal openings suggesting complex disease.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides detailed soft tissue visualization without radiation exposure, making it a standard for complex fistula mapping. MRI accurately delineates the primary tract, identifies secondary extensions, and reveals hidden abscesses. The imaging clearly shows the fistula’s relationship to the sphincter complex, guiding surgical planning and reducing unexpected operative findings.

Endoanal ultrasound uses a rotating probe inserted into the anal canal to create 360-degree images of the sphincter complex and surrounding tissues. The technique excels at identifying internal openings and sphincter defects from previous surgery. Hydrogen peroxide injection through the external opening enhances tract visualization by creating hyperechoic bubbles within the fistula.

Fistulography involves injecting contrast material through the external opening followed by X-ray imaging. While this older technique has largely been replaced by MRI, it occasionally helps when MRI is contraindicated or unavailable. The procedure poorly demonstrates the fistula’s relationship to the sphincter muscles and misses secondary tracts in many cases.

Examination under anesthesia allows thorough assessment when office examination proves inadequate due to pain or patient anxiety. The surgeon can probe the tract, identify internal openings using dye injection, and assess sphincter integrity without causing discomfort.

Treatment Options

Surgical Treatments

Fistulotomy is a standard treatment for simple intersphincteric and low transsphincteric fistulas, achieving good healing rates. The procedure involves opening the entire fistula tract from internal to external opening, converting the tunnel into an open groove that heals by secondary intention. The surgeon carefully divides any involved sphincter muscle, with the amount of muscle division determining continence risk. Healing typically requires 6-12 weeks, with regular wound care preventing premature skin bridging.

Seton placement manages complex fistulas through staged treatment or long-term drainage. A cutting seton—usually a silk suture or rubber band—gradually cuts through the sphincter muscle over 6-12 weeks, allowing fibrosis to maintain continence. Loose setons provide chronic drainage without muscle division, controlling sepsis while preserving sphincter function. This approach suits patients with Crohn’s disease or those at high continence risk.

Advancement flap procedures preserve sphincter integrity by covering the internal opening with healthy tissue. The surgeon creates a flap of rectal mucosa, advances it over the internal opening, and secures it below the original opening site. The external tract is curetted and left to heal. This procedure shows moderate success rates, with failure often allowing repeat attempts or alternative procedures.

LIFT (Ligation of Intersphincteric Fistula Tract) procedure approaches the fistula through the intersphincteric plane, ligating and dividing the tract while preserving both sphincters. The surgeon identifies the tract between the internal and external sphincters, secures it with sutures, and removes the infected tissue. This procedure shows good healing rates with minimal impact on continence even when the procedure fails.

Fibrin glue injection offers a minimally invasive option with no risk to continence. After tract curettage, commercial fibrin glue fills the fistula, theoretically promoting healing through clot formation and fibroblast migration. Success rates remain modest, though the procedure’s safety allows multiple attempts.

Fistula plug insertion uses biological collagen material to occlude the tract while providing a scaffold for tissue ingrowth. The plug is secured at the internal opening and trimmed flush with the external opening. This procedure shows moderate success rates, with some plugs extruding before healing occurs.

Non-Surgical Management

Conservative management rarely cures chronic fistulas but may provide symptom control for poor surgical candidates or those refusing operation. Regular sitz baths—sitting in warm water for 10-15 minutes three times daily—may improve hygiene and provide comfort. The warm water increases blood flow, reduces muscle spasm, and helps drainage from the external opening.

Wound care focuses on keeping the external opening clean and protecting surrounding skin. Gentle cleansing with water after bowel movements, followed by thorough drying, prevents maceration. Barrier creams containing zinc oxide protect perianal skin from moisture and irritation.

Dietary modifications aim to regulate bowel habits and reduce straining. Fiber supplementation creates formed stools that pass easily without traumatizing the fistula. Adequate hydration helps maintain stool softness, while avoiding foods that cause diarrhea prevents frequent irritation of the tract.

Recovery and Post-Operative Care

Post-fistulotomy wounds require careful care to ensure healing from the base upward. Daily wound irrigation with warm water removes debris and promotes granulation tissue formation. Patients perform sitz baths after each bowel movement and before bedtime, with some adding salt or antiseptic solutions though plain water suffices.

Pain management may involve oral analgesics for 7-14 days, with requirements decreasing as healing progresses. Topical anesthetic ointments applied before bowel movements may reduce discomfort during the first week. Muscle relaxants may help patients with significant sphincter spasm.

Wound packing prevents premature skin closure over deeper tissues, though excessive packing delays healing. Light gauze placement absorbs drainage without impeding granulation tissue formation. Packing requirements decrease as the wound contracts, eventually transitioning to simple gauze coverage.

Activity restrictions vary by procedure extent, with most patients returning to desk work within one week. Heavy lifting and strenuous exercise wait 2-4 weeks to prevent wound disruption. Sexual activity resumes when comfortable, typically after 2-3 weeks for simple fistulotomy.

Follow-up appointments occur weekly initially, then biweekly as healing progresses. The surgeon monitors wound healing, adjusts care instructions, and addresses any complications. Complete healing takes 6-12 weeks for simple fistulotomy, longer for complex procedures.

Complications and Risk Factors

Fistula recurrence can occur, with higher rates for complex fistulas. Inadequate identification of the internal opening, missed secondary tracts, or premature skin healing over residual infection cause most recurrences. Repeat imaging and examination under anesthesia help identify the failure mechanism and guide revision surgery.

Incontinence remains a significant complication, ranging from minor gas leakage to complete loss of bowel control. Risk factors include:

- Previous fistula surgery

- High transsphincteric fistulas

- Female gender

- Anterior fistula location

Sphincter-preserving procedures reduce but don’t eliminate continence risks.

Delayed wound healing occurs when infection persists, nutrition is poor, or local factors impair tissue repair. Diabetes, immunosuppression, and smoking significantly slow healing. Some wounds require several months for complete closure, testing patient patience and compliance with wound care.

Living with Chronic Anal Fistula

Daily hygiene routines become important for managing drainage and preventing skin complications. Patients develop personalized strategies including carrying supplies for cleanup, using panty liners or gauze pads, and timing activities around drainage patterns. Portable bidets or wet wipes facilitate cleansing when away from home.

Dietary adjustments help regulate bowel function and minimize fistula irritation. Identifying trigger foods that cause diarrhea or excessive gas allows patients to modify their diet accordingly. Probiotic supplements may improve stool consistency and reduce inflammation.

Work accommodations might include frequent bathroom breaks, ergonomic seating to reduce pressure, and flexibility for medical appointments. Open communication with employers about medical needs, without necessarily disclosing specific details, helps secure necessary support.

Intimate relationships require honest discussion about the condition’s impact on physical comfort and emotional wellbeing. Partners benefit from understanding the medical nature of the condition and ways they can provide support during treatment and recovery.

Commonly Asked Questions

How long does a chronic anal fistula take to heal after surgery?

Simple fistulotomy wounds typically heal within 6-12 weeks, though complex fistulas may require 3-4 months. Healing time depends on the fistula size, surgical technique used, and individual factors like nutrition and smoking status. Regular wound care and follow-up appointments support healing progression.

Can a chronic anal fistula heal without surgery?

Chronic fistulas rarely heal spontaneously once the tract becomes epithelialized. While symptoms may temporarily improve with conservative management, the underlying tract persists and typically continues causing problems. Surgical intervention offers a reliable treatment option for established chronic fistulas.

What activities should I avoid with an anal fistula?

Avoid prolonged sitting on hard surfaces, which increases pressure and discomfort. Heavy lifting and strenuous exercise may worsen symptoms or delay post-surgical healing. Constipation and straining during bowel movements should be prevented through dietary modification and stool softeners when needed.

Will I need multiple surgeries for my fistula?

Simple fistulas usually require single-stage surgery, while complex fistulas may need staged procedures to preserve continence. Initial seton placement followed by definitive repair, or sequential LIFT procedure after failed fistulotomy, represent common multi-stage approaches.

How can I prevent fistula recurrence after surgery?

Maintain soft, formed stools through adequate fiber and hydration. Complete the prescribed wound care regimen to support proper healing. Address underlying conditions like Crohn’s disease that predispose to fistula formation. Attend all follow-up appointments for early detection of any healing problems.

Conclusion

Chronic anal fistulas require specialized evaluation to determine appropriate treatment approaches. Surgical intervention offers the most reliable path to healing, though selecting the right procedure depends on fistula type and patient factors. Success requires collaboration between patient and surgeon throughout treatment and recovery.

If you’re experiencing persistent anal drainage, recurring abscesses, or pain around the anal area, a colorectal surgeon can provide comprehensive evaluation and treatment planning.